Art forgery has been around since, well, art. The ancient Romans crafted thousands of copies of Greek sculptures; ancient China is noted for its wide variety of forgeries, and modern art has seen more than its share of falsified work. Some forgeries are innocent enough, usually created by students copying a master, but others were created with the sole purpose of tricking an unsuspecting public into thinking they were the real deal. Some forgers are so good at what they do that it’s virtually impossible to tell the difference between the original and the copy – leading to many museums, investors and galleries putting millions into complete fakes.

There have been thousands of documented cases of fraudulent works of art over the centuries. But here are some of the examples that involve the biggest battles over authentication, the strangest stories, and most famous artists in art history.

La Bella Principessa attributed to Leonardo da Vinci

Depending on who you ask, this painting is either a priceless masterpiece by Leonardo da Vinci or a highly skilled copy worth just $20,000. The authenticity of this work has been a hotly contested topic since 2008 when art dealer Peter Silverman claimed he discovered it in the drawer of a Parisian friend’s home. The story, while romantic in nature, was untrue seeing as how the work had been auctioned and sold to Silverman several years previously.

Despite initial excitement about the work, as new ones by Leonardo rarely come on the market, the story might have ended there. However, several noted art historians and art experts came to support the theory that it might not be that of Leonardo. These experts claim to have science on their side, but so do their detractors and both have produced compelling evidence in support of their positions. The debate over the authenticity of this work could rage on indefinitely, but one thing is sure; whether the work was done by Leonardo or another artist, it’s a beautiful and skillfully drawn portrait.

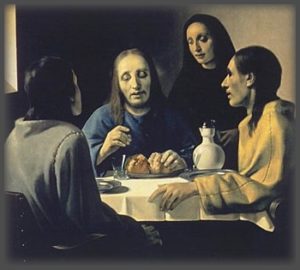

Christ and the Disciples at Emmaus attributed to Vermeer

This painting was at the center of one of the most amazing art scandals of the 20th century. During WWII, the painting was brought to the attention of noted Vermeer expert Abraham Bredius, who upon seeing the work thought it could be none other than the genuine article and one of Vermeer’s most masterful works. Little doubt was expressed by the public regarding this opinion due to the respected position of Bredius and the relative obscurity of Vermeer at the time. The painting might have gone unnoticed as a forgery had the war not been going on. The forger of the work,

This painting was at the center of one of the most amazing art scandals of the 20th century. During WWII, the painting was brought to the attention of noted Vermeer expert Abraham Bredius, who upon seeing the work thought it could be none other than the genuine article and one of Vermeer’s most masterful works. Little doubt was expressed by the public regarding this opinion due to the respected position of Bredius and the relative obscurity of Vermeer at the time. The painting might have gone unnoticed as a forgery had the war not been going on. The forger of the work,

Han Van Meegeren was charged with collaborating with the enemy for selling what was believed to be an original Vermeer to Nazi Field Marshall Hermann Goering. To escape the death sentence this accusation held, Van Meegeren claimed that this painting was a forgery. To prove it, he painted another copy of Vermeer’s work under police guard. It turns out that he had not only forged these works but at least16 others through an ingenious process of painting and aging that allowed him to trick even the most knowledgeable art experts, duping them out of over $30 million in today’s money.

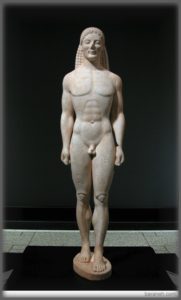

The Getty Kouros

The Getty Museum has a bit of a reputation for buying works that are of questionable provenance and the Kouros, purchased in 1985 for $7 million is no exception. Initially, the work was regarded as authentic through scientific analysis of the marble, yet it has been demonstrated that it is possible to age the stone by an artificial method, throwing the authenticity of the piece into question.

The Getty Museum has a bit of a reputation for buying works that are of questionable provenance and the Kouros, purchased in 1985 for $7 million is no exception. Initially, the work was regarded as authentic through scientific analysis of the marble, yet it has been demonstrated that it is possible to age the stone by an artificial method, throwing the authenticity of the piece into question.

Further damning it is the assertions of several art historians that something simply isn’t right about the piece as it has a highly electric style that blends characteristics from several other known kouroi and displays inaccuracies in sculpting, motion, and symmetry of the figure. The Getty has subsequently had more studies done on the piece to prove it’s authenticity, but most scholars today believe the work to be a forgery. The sculpture is still on exhibit in the Getty with the label, “Greek, about 530 B.C., or modern forgery.”

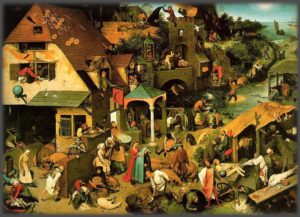

The Netherlandish Proverbs attributed to Pieter Bruegel the Elder

We often think of forgeries taking place many years after the artist has passed away, but popular artists have often reproduced within their own lifetimes and very soon afterward. In this case, the copyist was Breugel’s own son, Pieter Brueghel the Younger. This younger artist made numerous copies of his father’s work, including this popular painting, as well as a landscape that now hangs in the Delporte Collection in Brussels.

We often think of forgeries taking place many years after the artist has passed away, but popular artists have often reproduced within their own lifetimes and very soon afterward. In this case, the copyist was Breugel’s own son, Pieter Brueghel the Younger. This younger artist made numerous copies of his father’s work, including this popular painting, as well as a landscape that now hangs in the Delporte Collection in Brussels.

Most interestingly, not all copies the son made of this father’s work include the same proverbs, and often are not exact copies. While imitation is the most sincere form of flattery, in this case it served to confuse and perhaps mislead art buyers. While Brueghel spent many years copying his father’s works, he also enjoyed a successful career in his own right, painting similar scenes though many say, without the same subtlety and humanism as that of his father and in a much more idealized manner.

Portrait of Alexander Mornauer attributed to Hans Holbein

This portrait further proves that even major museums can make mistakes when it comes to collecting fake works. At face value, this work appeared to be the product of well-known German artist Hans Holbein the Younger when it was purchased by the National Gallery in London. Yet it had been altered during the 18th century, a time when Holbein’s work was in great demand.

This portrait further proves that even major museums can make mistakes when it comes to collecting fake works. At face value, this work appeared to be the product of well-known German artist Hans Holbein the Younger when it was purchased by the National Gallery in London. Yet it had been altered during the 18th century, a time when Holbein’s work was in great demand.

A layer of paint over the original changed the color of the background and altered the man’s hat, something that didn’t come to light until the work could be examined through modern methods. Oddly enough, the work is just as valuable as an anonymous work than as a Holbein, as portraits from this period aren’t common. The work was recently exhibited in a show entitled “Close Examination: Fakes, Mistakes and Discoveries.”

An Allegory attributed to Sandro Botticelli

In 1874, the National Gallery purchased two works attributed to iconic Italian painter Sandro Botticelli, well before the advent of modern authentication technologies. One of these paintings, Venus and Mars turned out to be authentic and is one of the museum’s most prized paintings. Yet the other, though at the time to be a companion painting to Venus and Mars, was discovered to be done by a follower in the style of the master, rather than by Botticelli himself. While still skillfully executed, the work doesn’t have the value or the prestige afforded to Botticelli’s work. Ironically, the museum paid more for the fake than for the real thing.

In 1874, the National Gallery purchased two works attributed to iconic Italian painter Sandro Botticelli, well before the advent of modern authentication technologies. One of these paintings, Venus and Mars turned out to be authentic and is one of the museum’s most prized paintings. Yet the other, though at the time to be a companion painting to Venus and Mars, was discovered to be done by a follower in the style of the master, rather than by Botticelli himself. While still skillfully executed, the work doesn’t have the value or the prestige afforded to Botticelli’s work. Ironically, the museum paid more for the fake than for the real thing.

The Freida Kahlo Archive

It’s not necessarily uncommon for one or two works by an artist to be found to be fake, but it’s very strange indeed when an entire collection of paintings, letters, and belongings are called out as being inauthentic– but that’s just what happened in this case. The collection came to light in 2009 when a book was slated to be published about the 1,200 or so articles it contains. Art historians, dealers, artists, bloggers, and Kahlo experts have come out to denounce the collection, saying it’s full of fakes and that the owners are either victims or perpetrators of one of the biggest hoaxes in art history.

It’s not necessarily uncommon for one or two works by an artist to be found to be fake, but it’s very strange indeed when an entire collection of paintings, letters, and belongings are called out as being inauthentic– but that’s just what happened in this case. The collection came to light in 2009 when a book was slated to be published about the 1,200 or so articles it contains. Art historians, dealers, artists, bloggers, and Kahlo experts have come out to denounce the collection, saying it’s full of fakes and that the owners are either victims or perpetrators of one of the biggest hoaxes in art history.

The collectors, The Noyolas, claim that these experts simply don’t want to alter the public image of Kahlo, something they believe this collection just might do. Proof exists on both sides as few experts have taken a close look at the collection but the provenance of many of the items is shaky at best. Only time will tell whether or not this archive goes down as an amazing discovery or an amazing forgery.

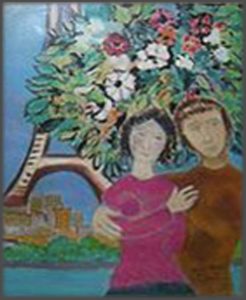

Watercolors attributed to Marc Chagall

In the 1960s, a young art dealer named David Stein sold three watercolors, purportedly by Russian artist Marc Chagall to an art dealer in New York. The works weren’t authentic, however, as Stein had painted them that day and created forged letters of authentication as well. Stein may have got off scot-free if it had not been for a chance occurrence.

In the 1960s, a young art dealer named David Stein sold three watercolors, purportedly by Russian artist Marc Chagall to an art dealer in New York. The works weren’t authentic, however, as Stein had painted them that day and created forged letters of authentication as well. Stein may have got off scot-free if it had not been for a chance occurrence.

Marc Chagall just happened to meet with the dealer who bought those watercolors on that very same day, immediately revealing that they were fakes. Stein went on to serve several years in prison but the incident boosted his reputation so much that he was able to strike up a career as an original artist upon his release.

Sculptured Tomb attributed to Mino da Fiesole

Alceo Dossena was one of the most famous forgers of sculpture in the 20th century, carving many masterful reproductions of everything from Greek statues to Renaissance tombs. Dossena and his dealers successfully fooled art buyers, galleries and museums around the world that his work was that of artists like Pisano, Martini, and Donatello– very clearly demonstrating his high level of skill as a forger.

Alceo Dossena was one of the most famous forgers of sculpture in the 20th century, carving many masterful reproductions of everything from Greek statues to Renaissance tombs. Dossena and his dealers successfully fooled art buyers, galleries and museums around the world that his work was that of artists like Pisano, Martini, and Donatello– very clearly demonstrating his high level of skill as a forger.

One such work, a sculptured tomb attributed to Mino da Fiesole eventually made its way to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts– a costly mistake for the museum as they paid $100,000 for the forgery. Dossena, frustrated by his dealers taking nearly all of the profits revealed the ruse and sued his dealers, claiming he was unaware the works were being sold under false pretenses. He was cleared of all charges and went back to creating original works. The museum refused to believe the tomb was a fake until Dossena produced photographs of it in progress. Many of his works are thought to still be out there, circulating as genuine articles.

Henri Leroy attributed to Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot

To limit forgeries to this artist to only one work is hard, but this particular forgery is done by one of the most masterful forgers of all time making it stand out. Forgeries of Corot’s works are not uncommon. In fact, some suspect that he is the most widely forged artist of all time, producing only 3,000 works in his lifetime while over 100,000 works in the United States alone are attributed to him. It might have something to do with his willingness to let others borrow original works to copy for study or his style that is relatively easy to emulate.

To limit forgeries to this artist to only one work is hard, but this particular forgery is done by one of the most masterful forgers of all time making it stand out. Forgeries of Corot’s works are not uncommon. In fact, some suspect that he is the most widely forged artist of all time, producing only 3,000 works in his lifetime while over 100,000 works in the United States alone are attributed to him. It might have something to do with his willingness to let others borrow original works to copy for study or his style that is relatively easy to emulate.

Regardless, this particular forgery is a masterful one done by Eric Hebborn, and after being caught published a book on his life as a forger. In it, he showcases his copy of Corot’s work alongside the original, challenging art experts to tell the difference. And that was the problem. Hebborn was so good at forging works that the art market is still haunted by doubts that seemingly authentic works could, in fact, be his handiwork. To this day, he is regarded for this work and the thousands of others he completed in his lifetime, as one of the best forgers of all time.