It is difficult to understand today, but the paintings of the PRB were seen as shocking in their day, and critics were harsh in their condemnation, in particular, the writer Charles Dickens. John Ruskin became the champion of the Pre-Raphaelites, writing a series of famous letters to The Times in support of their paintings, and this marked a change in attitude, by some of the PRB painters themselves (Millais even eventually became President of the Royal Academy), and by the artistic establishment and the general public. By 1853, the original Brotherhood had disbanded, and Pre-Raphaelitism was to be carried onwards to its next phase through the work of Rossetti and Burne-Jones. Other artists (e.g. Frank Cadogan Cowper & Maxwell Armfield) continued to be inspired by the movement well into the 20th century.

The first thing likely to strike anyone looking at poems and paintings by Pre-Raphaelite artists is that they have little in common. The label “Pre-Raphaelite” leads a reader or viewer to expect some uniformity arising from a common aesthetic philosophy, technique, or goal, but the Pre-Raphaelites rarely provide such uniformity, despite the heroic efforts of later critics to locate it. Even within the literary and artistic work of a given member, it is easy to find a variety of styles and approaches that prevents easy generalizations.

Yet it would be wrong to conclude that the term “Pre-Raphaelite” is meaningless. On the contrary, the phenomenon of the group label is one of the most interesting things about the Pre-Raphaelites, even though the artists who originally came up with the name did so in a relatively joking spirit. Early in the nineteenth century, when labels had been applied to groups of artists, they were often a dismissive mark of hostile criticism. The point of the criticism was that great artists did not belong to schools, either because they were individual geniuses who transcended group identities or because all good artists recognized common, well-established aims, so that forming a distinctive school was a mark of inferior artistry. Nothing is more important about the Pre-Raphaelites than their ability to turn the group label, which had been an image in criticism for inferior art, into a self-conscious badge of rebellion.

Yet it would be wrong to conclude that the term “Pre-Raphaelite” is meaningless. On the contrary, the phenomenon of the group label is one of the most interesting things about the Pre-Raphaelites, even though the artists who originally came up with the name did so in a relatively joking spirit. Early in the nineteenth century, when labels had been applied to groups of artists, they were often a dismissive mark of hostile criticism. The point of the criticism was that great artists did not belong to schools, either because they were individual geniuses who transcended group identities or because all good artists recognized common, well-established aims, so that forming a distinctive school was a mark of inferior artistry. Nothing is more important about the Pre-Raphaelites than their ability to turn the group label, which had been an image in criticism for inferior art, into a self-conscious badge of rebellion.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (or P.R.B.) was founded in 1848. It was an association of young English artists who tried to distance themselves from the frivolous subject matter of official painting and seek “truth in nature”. To do this, they concentrated upon a new style of painting, returning to simplicity in artist procedures, giving new importance to the craftsmanship of the past, modelling their work after the primitive Italians, the artists of the Quattrocento and painters who worked before Raphael. Their influences included the romance of medieval chivalry, religion, literature and also contemporary Victorian society.

The Royal Academy, founded in 1768, had been a critical institution for raising the respectability of painting and of painters in Britain as a professional class. In the nineteenth century, it continued under the burden of representing British national values, especially in the paintings that the Academicians chose for public exhibition. Yet the actual education given to the students at the Royal Academy was relatively uninspiring: students spent months copying works, receiving occasional criticisms from teachers, and hearing dry lectures on such topics as perspective or art history.

The Royal Academy, founded in 1768, had been a critical institution for raising the respectability of painting and of painters in Britain as a professional class. In the nineteenth century, it continued under the burden of representing British national values, especially in the paintings that the Academicians chose for public exhibition. Yet the actual education given to the students at the Royal Academy was relatively uninspiring: students spent months copying works, receiving occasional criticisms from teachers, and hearing dry lectures on such topics as perspective or art history.

Original Members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

- James Collinson

- William Holman Hunt

- Sir John Everett Millais

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti

- William Michael Rossetti

- Frederick George Stephens

- Thomas Woolner

Other Artists who painted in Pre-Raphaelite style in the 1850s

- John Brett

- Ford Madox Brown

- William Shakespeare Burton

- Charles Allson Collins

- Walter Howell Deverell

- William Dyce

- Augustus Leopold Egg

- Arthur Hughes

- John William Inchbold

- Henry Wallis

Given the Academy’s claustrophobia, it was hardly surprising that some young students would be eager to rebel against its strictures. Three gifted artists studying there, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt, and John Everett Millais, agreed to create a secret society dedicated to taking the arts in a new direction. Later, Rossetti’s brother William Michael, a critic; the sculptor Thomas Woolner; and the painters James Collinson and Frederic George Stephens joined the group. Rossetti’s teacher and lifelong friend, Ford Maddox Brown, part of an older generation of painters, was also closely associated with it, though he was never an actual member. The adjective “Pre-Raphaelite” seems to have been Hunt’s idea, while Rossetti added the “Brotherhood.” Rossetti’s Girlhood of Mary Virgin (1849) was the first painting to include the actual initials “PRB” after his signature to denote membership in the group. Although what the initials stood for was supposed to be secret, their meaning quickly became common knowledge once the paintings began to attract the attention of art critics in London.

Given the Academy’s claustrophobia, it was hardly surprising that some young students would be eager to rebel against its strictures. Three gifted artists studying there, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt, and John Everett Millais, agreed to create a secret society dedicated to taking the arts in a new direction. Later, Rossetti’s brother William Michael, a critic; the sculptor Thomas Woolner; and the painters James Collinson and Frederic George Stephens joined the group. Rossetti’s teacher and lifelong friend, Ford Maddox Brown, part of an older generation of painters, was also closely associated with it, though he was never an actual member. The adjective “Pre-Raphaelite” seems to have been Hunt’s idea, while Rossetti added the “Brotherhood.” Rossetti’s Girlhood of Mary Virgin (1849) was the first painting to include the actual initials “PRB” after his signature to denote membership in the group. Although what the initials stood for was supposed to be secret, their meaning quickly became common knowledge once the paintings began to attract the attention of art critics in London.

To further consolidate the group’s identity, the members planned a periodical entitled The Germ: Thoughts Towards Nature in Literature, Poetry, and Art. Although The Germ lasted only four issues, it was notable in several respects. Unlike almost any other periodical of the day, it featured mostly poetry and essays on aesthetics, rather than the standard fare of book reviews, political essays, or serializations. It was an “in-group” publication, by artists for artists, as was underscored by the title chosen for its last two issues: Art and Poetry: Being Thoughts Towards Nature, Conducted Principally by Artists. It also broadened the significance of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood by insisting that its importance was not confined solely to painting: it included literature and essays on aesthetics as well. An organ through which to formulate an aesthetic manifesto and to expand into other modes increased the perceived intellectual seriousness and weight of the Pre-Raphaelites’ endeavors. In it, important early poems by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (“The Blessed Damozel” and “My Sister’s Sleep”) and Christina Rossetti (“Dream Land”) first appeared, as well as essays on art by Frederic George Stephens and Ford Maddox Brown. The core of the Pre-Raphaelites’ program in some ways recalled that of Wordsworth; their goal was “an endeavour to encourage and enforce an entire adherence to the simplicity of nature” (Rossetti, 1851, p. [X2]). Yet the Pre-Raphaelites’ invocation of nature, especially in relation to painting, had a particular edge, though not one made explicit in their manifestos: art had to recognize the challenge posed by technical developments in photography by developing higher standards of verisimilitude.

To further consolidate the group’s identity, the members planned a periodical entitled The Germ: Thoughts Towards Nature in Literature, Poetry, and Art. Although The Germ lasted only four issues, it was notable in several respects. Unlike almost any other periodical of the day, it featured mostly poetry and essays on aesthetics, rather than the standard fare of book reviews, political essays, or serializations. It was an “in-group” publication, by artists for artists, as was underscored by the title chosen for its last two issues: Art and Poetry: Being Thoughts Towards Nature, Conducted Principally by Artists. It also broadened the significance of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood by insisting that its importance was not confined solely to painting: it included literature and essays on aesthetics as well. An organ through which to formulate an aesthetic manifesto and to expand into other modes increased the perceived intellectual seriousness and weight of the Pre-Raphaelites’ endeavors. In it, important early poems by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (“The Blessed Damozel” and “My Sister’s Sleep”) and Christina Rossetti (“Dream Land”) first appeared, as well as essays on art by Frederic George Stephens and Ford Maddox Brown. The core of the Pre-Raphaelites’ program in some ways recalled that of Wordsworth; their goal was “an endeavour to encourage and enforce an entire adherence to the simplicity of nature” (Rossetti, 1851, p. [X2]). Yet the Pre-Raphaelites’ invocation of nature, especially in relation to painting, had a particular edge, though not one made explicit in their manifestos: art had to recognize the challenge posed by technical developments in photography by developing higher standards of verisimilitude.

Though the results may seem less innovative now than they did in the 1850s, early viewers responded with real shock. Innovation and experimentation were not what they had come to expect from the staid exhibitions of the Royal Academy. Although early reviews were scorching, the Pre-Raphaelites were lucky to find a somewhat unexpected champion in the most distinguished aesthetician of the age, John Ruskin, who, as the scholar Isobel Armstrong notes, “probably managed to give … a more coherent account of Pre-Raphaelite principles than they could themselves” (Armstrong 1993, p. 233). Partly through the prestige of Ruskin’s work, hostility toward the Pre-Raphaelites diminished rapidly, and they quickly became some of the most praised artists of the day. The close association of the Brotherhood, however, was over by 1853.

Italian Renaissance painter Raphael

While the label “Pre-Raphaelite” came to be something of an embarrassment for most in the Brotherhood, it deserves careful scrutiny. It was a self-consciously difficult term, one that presupposed considerable knowledge about the history of European art. The Italian Renaissance painter Raphael (1483–1520) had long been held up in England and in the Royal Academy as the model for aspiring artists. In a peculiar twist of events, a set of cartoons that he produced as designs for tapestries had an extraordinary afterlife in England; they were copied as paintings for Hampton Court, widely disseminated through engravings and copies, and became models for neoclassical taste. Lecture after lecture at the Royal Academy held up Raphael and his cartoons as ideals and as the source for what were easily felt to be arbitrary rules about good painting: all figures in a painting needed to be placed in an S-shape; the principal figure needed to have the most light; one corner always had to be in the shade; and others.

Raphaelitism

A suggestive ambiguity in the adjective “Pre-Raphaelite” characterizes exactly how the artists related themselves to Raphael. One interpretation is that the painters wished to associate themselves with whatever was before “Raphaelitism.” The members of the Brotherhood understood “Raphaelitism” as a shorthand for the perceived rigidification of Raphael’s influence, rather than for Raphael himself. As Holman Hunt wrote in his memoir, “Pre-Raphaelitism is not Pre-Raphaelism” (1905/1984, p. 23). The suffix “ite” marked the distinction in a mocking echo of Biblical usage (“Israelite,” “Canaanite,” “Moabite”), as if followers of Raphael were a lost tribe, keeping an allegiance to values sadly out of place in a modern setting. Through their label, the Pre-Raphaelites unmasked the Royal Academy’s precepts not as universally recognized aesthetic truths, but as products of a worn-out and derivative school, Raphaelitism.

In this context, the “pre-Raphaelite” had more of the force of “anti-Raphaelite” or even “post-Raphaelite.” The hallmark of this rejection of Raphaelitism in early Pre-Raphaelite paintings is an almost hallucinatory attention to detail, combined with the abandonment of traditional schemes for organizing painted figures, as in Holman Hunt’s The Awakening Conscience (1853–1854) and Millais’s Ophelia (1851–1852). Such aggressive precision in the representation of detail was the quality most often noted by their early admirers. In their art, this realism went hand in hand with a marked assertion of Englishness, as if avoiding the “Raphaelite” meant avoiding turning away from the continent. Unlike J. M. W. Turner (1775–1851) and his famous images of Venice, the Pre-Raphaelites painted English people, English scenery, and scenes from English literature, so that even their Italian scenes, as in Holman Hunt’s Valentine Rescuing Sylvia from Proteus (1851), were from English authors. A notable facet of this Englishness was the willingness of the Pre-Raphaelites to champion English poets who were still virtually unknown in Victorian Britain, including John Keats and William Blake.

Examples of early Pre-Raphaelite Paintings

Ford Madox Brown

- Chaucer at the Court of King Edward III (1845-51)

- Christ Washing Peter’s Feet (1851-56)

- Work (1852-65)

- The Pretty Baa-Lambs (1851-59)

Charles Allston Collins

- Convent Thoughts (1851)

James Collinson

- The Renunciation of Queen Elizabeth of Hungary (c.1848-1850)

Walter Howell Deverell

- Twelfth Night, Act II, Scene IV (1850)

Arthur Hughes

- Ophelia (1852)

- April Love (1855-56)

- The Eve of Saint Agnes (1856)

William Holman Hunt

- Rienzi (1849)

- A Converted British Family Sheltering a Christian Priest from the Persecution of the Druids (1850)

- Claudio and Isabella (1850)

- Valentine Rescuing Sylvia from Proteus (1851)

- The Hireling Shepherd (1851)

- Strayed Sheep (Our English Coasts) (1852)

- The Awakening Conscience (1853)

- The Light of the World (1853)

- The Scapegoat (1854)

Sir John Everett Millais

- Isabella (1849)

- Christ in the House of His Parents (1850)

- Mariana (1851)

- The Woodman’s Daughter (1851)

- Ophelia (1852)

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

- Ecce Ancilla Domini (1850)

- The First Anniversary of the Death of Beatrice (1853)

After the Brotherhood

While “Pre-Raphaelite” could signal a rebellion against Raphaelitism, it also had a different meaning, in which it denoted instead a self-conscious imitation of artists who came before Raphael. In this reading, discarding the Academy’s promotion of Raphael pointed to medieval art as a preferable model. In fact, few of the Brotherhood had direct contact with early Italian art, for very little of it was available for viewing in England, and most of the painters had not traveled on the Continent to see it. Nevertheless, The Germ foregrounded the medievalizing aspects of the label through such works as Rossetti’s Hand and Soul, a short historical fiction imagining the life and struggles of a medieval Italian painter, and Frederic George Stephens’s essay on early Italian art. The choice of the term “Brotherhood” itself was also a potentially medievalizing gesture, insofar as it gave the group defiantly Catholic associations, in a period when the Oxford movement had given Catholicism a particular allure as intellectual forbidden fruit.

This medievalism emerged most strongly after the breakup of the initial Brotherhood in 1853, when Rossetti and some fellow artists traveled to Oxford in the summer of 1857 to paint Arthurian murals on the walls of the Oxford Union Society. Unfortunately, they did not prepare the walls of the Union well for mural painting, and their work began to decay almost immediately. What mattered more was that, while at Oxford, Rossetti cemented his already existing friendships with the artist Edward Burne-Jones and the artist and poet William Morris, and that he met Algernon Charles Swinburne, who nearly a decade later would emerge as the most famous and scandalous poet in England. Whereas no single member of the original Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood had really stood out as a leader, the second wave of Pre-Raphaelitism was dominated by Rossetti. The young Oxfordians copied Rossetti so exactly that they started a journal like The Germ, the Oxford and Cambridge Magazine, which lasted for twelve issues; it even reprinted Rossetti’s “The Blessed Damozel” from The Germ.

Victorians and the Pre-raphaelites

As the subject of the Union murals indicates, medievalism was a more prominent, though never exclusive, motif in the second wave of Pre-Raphaelitism than it had been for the Brotherhood itself. Elsewhere in Victorian literature, medievalism came burdened with a heavy weight of political and religious associations. Thomas Carlyle had used the chronicle of a medieval abbey as a model for charismatic leadership in Past and Present (1843); John Ruskin in “The Nature of the Gothic” in The Stones of Venice (1851) had treated the perceived grotesqueness of medieval art as a model of unalienated labor. The Pre-Raphaelite medievalism of Rossetti, Morris, and Burne-Jones is often seen, in contrast, as a dreamy escape from contemporary reality into a fantasy past. But for the Pre-Raphaelites, the medieval was less an escape into fantasy than a representational style that let them reject mid-Victorian conventions of didacticism, religiosity, domesticity, and sentimentality. After the tortured psychological self-examinations of poets like Tennyson or Arnold, poems like Rossetti’s “Sister Helen” and “The Staff and Scrip” or Morris’s “The Defence of Guenevere” and “The Haystack in the Floods” were refreshingly dry, impersonal, and even brutal. They drew instead on the conventions of the literary ballad as exemplified by writers like Walter Scott, in which action dominated character analysis. Far from being otherworldly fantasy, these poems cut through layers of respectable conventions to focus on tense drama and elemental passions.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Aside from medievalism, the other major development in the second wave of Pre-Raphaelitism was the growing artistic and intellectual significance of women. The most important woman writer associated with the Pre-Raphaelites was Dante Gabriel’s sister, Christina Rossetti, at once one of their closest associates and harshest critics. She published in The Germ and claimed to have benefited from her brother’s criticism of her poetry. Yet her poetry also offers a quiet but persistent critique of the Pre-Raphaelite treatment of female subjectivity. Her sonnet “In an Artist’s Studio” describes an artist who paints a woman “not as she is, but as she fills his dream,” thereby underlining the chasm between Pre-Raphaelite idealization and the actual woman involved. At the same time, it would be unfair to Christina Rossetti to view her work solely as a reflection on the work of the Pre-Raphaelites; her many books of theology, for example, need to be interpreted in quite different contexts. In addition to Christina Rossetti, many women artists contributed to the development of Pre-Raphaelitism, although their works were not always as publicly visible as those of the male artists: Rossetti’s wife Elizabeth Siddall; Joanna Boyce; Anna Mary Howitt; and others.

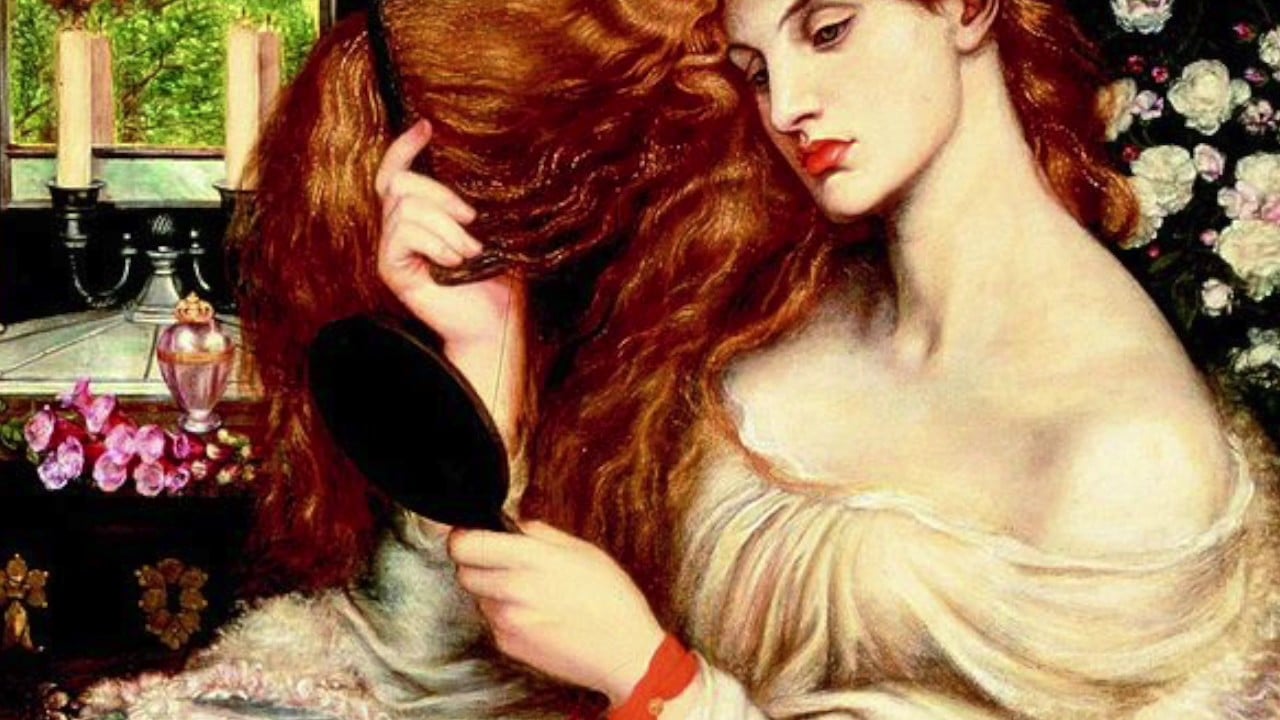

In the final decades of Rossetti’s life, partly at the instigation of his patrons, his paintings increasingly turned toward obsessive fixations on female beauty, the long succession of what Swinburne called “stunners.” He sold most of these paintings directly to patrons, often newly rich urban industrialists eager to distinguish themselves from an older, aristocratic tradition of collecting the works of European Old Masters. The paintings therefore received no public exhibition, increasing the aura of mystery around them. What may be most “stunning” today about this series of works is the eerie solitude of Rossetti’s women: they rarely have context outside themselves, and the poems that Rossetti sometimes wrote to accompany them only reinforces their solitude. The paintings rivet attention on female faces, perched precariously between haunting beauty, blank prettiness, and idiosyncratic ugliness; the label “Pre-Raphaelite” is often used to refer particularly to this distinctive feminine appearance. Details of Rossetti’s biography further heightened his mystique: his wild life in London, living at times with Swinburne, the poet and novelist George Meredith, and the painter Simeon Solomon; Siddall’s suicide in 1862; his burial of his poems with her—and the even more dramatic exhumation of them in 1869; his affair with Morris’s beautiful wife; the scandal created by the attack on his collected poems (1870) in Robert Buchanan’s essay “The Fleshly School of English Poetry” (1871); and his final descent into depression and drug addiction.

After Rossetti’s death in 1882, his reputation was consolidated by a range of reviews, memoirs, and evaluations. Although the work of many of those associated with Rossetti, including Swinburne, Meredith, and Morris, took quite different directions after their initial Pre-Raphaelite associations, Rossetti’s work itself did not go out of date as the century progressed, either because, as in the case of The Bride’s Prelude, he did not publish it until the end of his life or because, as in the case of “Sister Helen,” he continued to revise previously published versions. Moreover, much of Rossetti’s art was not widely known because it never received public exhibition. As a result, knowledge of his art acquired an enviable edge of distinction, since it was only available to a small elite. More than any other artist, he bridged the art of mid-Victorian Britain and the Aesthetic and Decadent movements of the fin de siècle: almost all the artists associated with these movements, including Oscar Wilde, Aubrey Beardsley, and William Butler Yeats, acknowledged their debt to Rossetti. Even T. S. Eliot, so often seen as a key figure in turning away from all that Rossetti represented, chose as the epigraph to his poem The Waste Land lines from Petronius that Rossetti had translated decades earlier.

More than any of the original Brotherhood could have predicted, the Pre-Raphaelite label turned out to be a canny piece of marketing. The aura of mystery surrounding the initials “PRB” fostered an explanation industry: commentaries, reviews, and evaluations that set out to teach the uninitiated just what Pre-Raphaelitism was. As early as the 1850s, this apparatus gave the Pre-Raphaelites a particular aura of intellectual rigor and interest, and it helps to explain how a rather small group of paintings and painters came to acquire such an enormous, unlikely influence. Dante Gabriel Rossetti, for example, became one of the most famous painters and poets in England, even though he had completed very few paintings or poems. Despite a revulsion against Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics in the first half of the twentieth century, Pre-Raphaelite images, with their unsettling ability to hover between kitsch and high art, have turned out to be one of the most enduring legacies of the Victorian era.

REFERENCE: Andrew Elfenbein