When, in 1919, Pierre Auguste Renoir died in the south of France, the critic Elie Faure wrote, “It is as if the sun had gone out of the sky”.

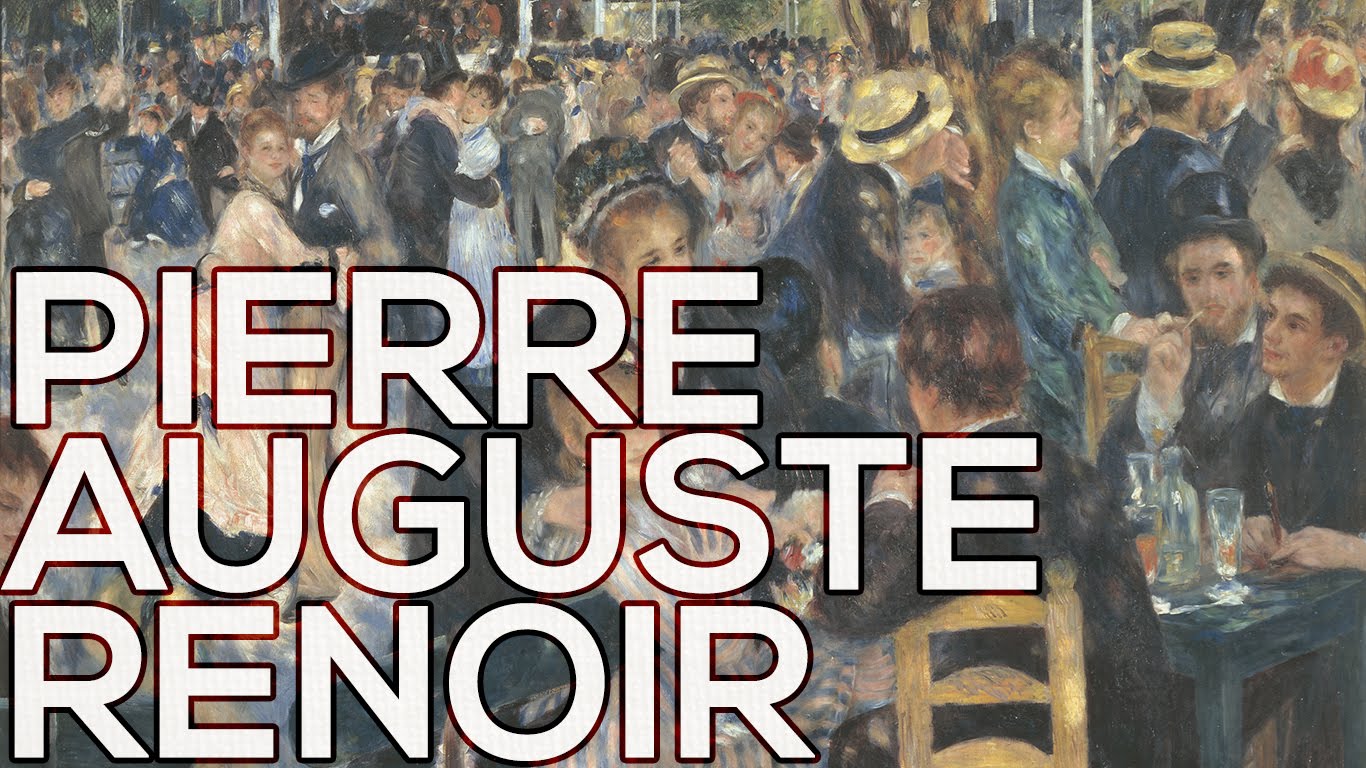

No other painter saw life so happily or caught more enchantingly the lyrical mood of Paris at the turn of the century. Renoir’s paintings remain a constant refreshment, the last great spontaneous song celebrating the good and natural things of life.

“First of all be a good craftsman. This will not keep you from being a genius.”

Renoir’s art is that of a man on good terms with life. His inspiration had its source in a sensuous delight in the world, and from his enchantment came a flow of paintings unrivalled in their lyricism. His art is never burdened with ideas or marked with conflict. As all true artists must, he transformed what he saw; but he saw with the eyes of a lover, and every element of his art affirmed his vision.

He was an amiable and uncomplicated man, free of disturbing tensions like those that give a sense of urgency, of painting as a refuge or comfort, to the works of some of his great contemporaries – Van Gogh, for example, or Degas. He painted with such relish that his pleasure in his craft and in his subjects is at once communicated to us, and we are moved to say that no other artist has painted so freely, so spontaneously, and with so much joy.

As a beginner, he was rebuked by Gleyre, a professor at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, with whom he had his only formal training in 1862 and 1863: “No doubt it’s to amuse yourself that you are dabbling in paint?” And Renoir answered, “Why certainly, and if it didn’t amuse me to paint, I beg you to believe that I wouldn’t do it”.

There probably was no impudence in Renoir’s answer: it must have struck him as strange that one might paint for any other reason.

Renoir’s art differs from that of other Impressionists: it is not simply a reflection of the pleasant aspects of life. We see it rather as the triumph of an ideal of happiness and beauty, and a victory over distress. It is remarkable that in the immense body of Renoir’s work – some estimate it at around four thousand pictures – there is no hint of darker, troubled moods.

He had early years of hardship, made more disturbing by political attacks because he, as an Impressionist, did not conform to conservative standards of art; there was a period of self-doubt (often disastrous for an artist) in the eighties; there were recurrent illnesses from the age of forty-one on, with the last fifteen years of his life a torment of arthritic pain.

For a few years before his death he was so crippled that he had to be carried about when he was not in his wheelchair, and his brush had to be strapped to his solidified hand. And yet, no trace of his personal suffering is anywhere to be seen in his work.

His art is always an affirmation. Instinctively he fixed on the happy aspects of the familiar things around him: the life of the streets; a beautiful day in the country; a bouquet of flowers or a profusion of fruits; people at play or making music; youth, and health. He was also responsive to the delicate flower freshness of small children, and he painted them as parents, with adorning incredulity, see their own.

He had a remarkable flair for recording his time, and though his pictures never sink to the level of illustration, they still are a marvellous account of how people looked, what they wore, and what they did in their carefree moments. And the overwrought taste of the later nineteenth century has an agreeable look in Renoir’s pictures, for he tempered its excesses while remaining true to its character.

Everything he touched he endowed with grace and charm. No other painter has discovered in the common actions of the human figure such vivacious gestures and attitudes, such piquant facial expressions.

If Renoir is not one of the deepest of portrait painters – though he is one of the most engaging, showing us his sitters as a kindly host would see them in his parlor – he is unsurpassed as a painter of the human figure, clothed or unclothed. The female nude, above all, was his subject – he almost never painted the more angular, structurally obvious male nude – because in it he found delights of color and texture, forms which were ample, and warmth and fruitfulness and the promise of joy.

Renoir started to earn money at painting when he was thirteen. His family had come to Paris from Limoges, where he was born, and Renoir was apprenticed as a painter of porcelain. Later he did pretty ornaments on fans and window shades, borrowing motifs from the French masters of the eighteenth century – Watteau, Boucher, and Fragonard – whom he was to admire all his life. This early experience, no doubt, assured the decorative grace that is always present in his work, as well as that lustrous glow of his pigment which attracts us as color-music.

“One learns to paint at the museum… One should paint for one’s own time. But it is at the museum that one acquires a taste for painting that nature alone does not provide.”

The realistic painting of the eighteen-sixties rooted him firmly in the substantial world; and as an Impressionist he discovered how to render the passing scene as spectacle, bathing his canvases in light, and filling them with a warmth of atmosphere that is all but palpable. He soon found that Impressionism was too limiting; subsequent works, show how he went beyond it. He never ceased to study the great art of the past, to which he was more closely attached than any artist of his generation – again an affirmation, this time of pleasure and nourishment found in the works of man.

When asked where one learned to paint, he said, “In the museums, parbleu!” His final work was in consonance with the spirit of twentieth-century painting: though he continued to image things, his lyricism was increasingly expansive and robust, inventive and daring, and Renoir came as close to an “abstract” colorist art as his devotion to things he loved would permit.

His greatness springs from his color, of an unparalleled radiance and originality, which modeled the forms by subtle passage from nuance to nuance; a love of pigment as a magical substance; a wonderfully simplified drawing which especially in his more mature work banishes the angular, the harsh, and the rigid; and his instinct for decorative composition.

Above all, there was his great love of people and the world; and the result was one of the most festive arts ever created.

Despite his severe physical disabilities, Renoir continued working up to the last year of his life. His great canvas in the Louvre, The Bathers, was completed in 1918. In 1917, he was visited by a young painter called Henri Matisse, who was destined to carry forward his ideas of color in into a new era.

Renoir died at Cagnes on 3 December 1919. He was 78 and recognised as one of the greatest of French painters.