Edgar Degas was born in Paris on 19 July 1834. He came from a wealthy banking family and had a standard upper-class education at the Lycée Louis le Grand. After briefly studying law, he elected to become an artist, working under approved masters and spending several years in Italy, then regarded as the “finishing school” of the arts.

“One must have a high opinion of a work of art – not the work one is creating at the moment, but of that which one desires to achieve one day. Without this it is not worthwhile working.”

By the 1860s Degas was already producing superb portraits, closely observed and characteristically original in composition. But his ambitions were still directed towards conventional success – in 19th century France this meant having pictures accepted to be shown at the official salon, which was virtually the only place where an artist could become known to the general public.

Consequently Degas painted the kind of works that had most prestige at the Salon: large, detailed set-pieces on historical topics such as The Young Spartans.

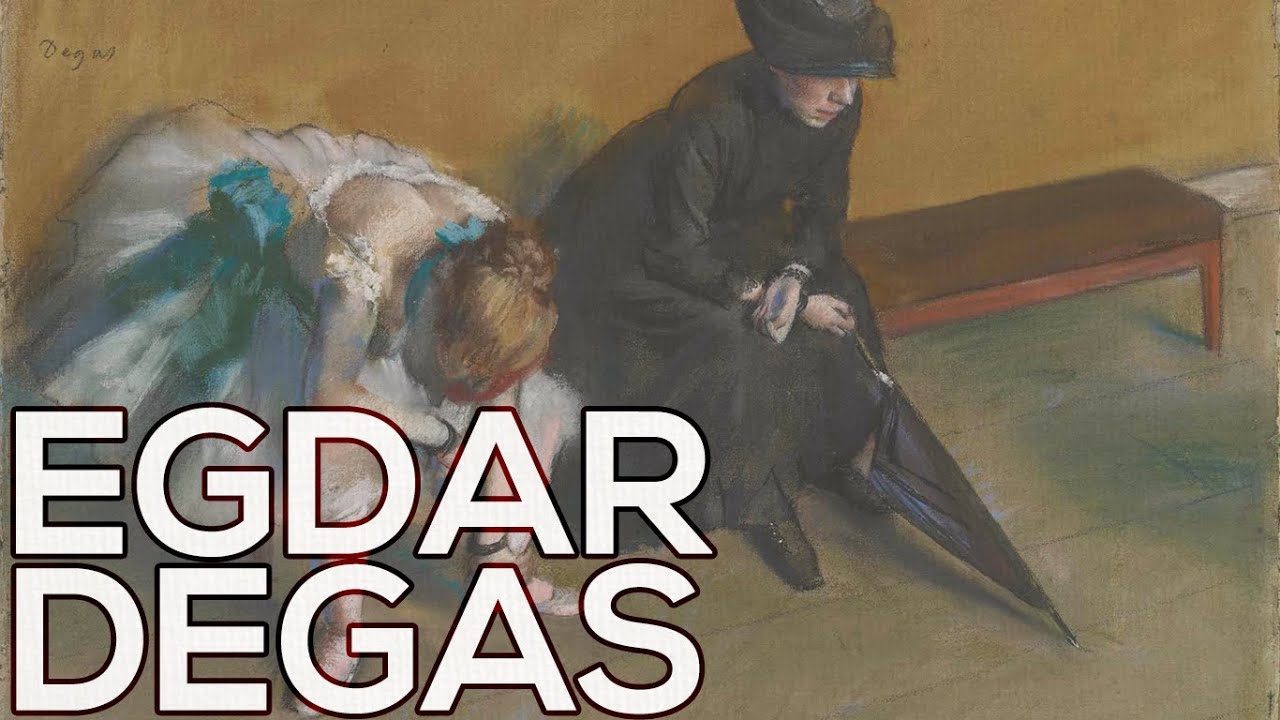

Only quite late in the 1860s did Degas begin to explore ‘modern’ subjects, which were regarded by the art establishment as rather trivial and lacking in nobility. However, Degas was somewhat behind his friend and rival Edouard Manet in becoming a ‘painter of modern life’, and he always restricted himself to a handful of subjects – portraits, the racecourse, the theatre, the orchestra, ladies at the milliner’s, laundresses, the nude, and above all the ballet.

He tackled each one again and again, often over long periods, constantly experimenting with new approaches; probably the closest analogy is with composers who produce sets of variations on a single theme. Miraculously, Degas is never stale, and his pictures bear a family resemblance without ever looking over-alike.

Degas’ techniques were highly original, although they owed something to the great 19th century vogue for Japanese prints and the up and coming art of photography. He portrayed his subjects from unusual angles (often from a very high viewpoint), almost always positioning them off-center; and instead of neatly tucking peripheral objects within the picture frame, he sliced straight through them. The effect is that of a snapshot, capturing a fleeting moment; the half-seen objects on the edge of the picture give the viewer the illusion that the scene continues beyond the frame. But although Degas’ pictures look spontaneous, they were actually carefully premeditated studio productions, built up from many sketches and studies. His was an art that concealed its artfulness.

Degas was an intensely private man, and his life was outwardly uneventful except for his service with the National Guard during the Prussian siege of Paris in 1870-1871. He made an extended visit to New Orleans to see his brothers in 1872-1873, but although he painted several pictures there, he ignored the exotic and specifically American sides of life in Louisiana, believing that an artist could only produce good work in his proper ambience.

In 1874 Degas made his most celebrated public gesture, becoming one of the principle organizers of an independent exhibition, held in opposition to the Salon.

Later it became known as the first Impressionist Exhibition, because of the prominent place taken by Monet, Renoir and other artists who were painting rapid, atmospheric landscape in the open air.

Degas rather disapproved of their work (he saw the exhibition as ‘a Realist Salon’), but he nevertheless contributed to all but one of the eight Impressionist shows between 1874 and 1886. Ironically, he is now often thought of as one of the Impressionists.

Even in the early 1870s Degas was having problems with his sight, and by the 1880s it was deteriorating alarmingly. But he continued to work hard, though increasingly in the less physically demanding medium of pastel. He achieved an undreamed-of variety of color and textural effects, and his work in pastels is as highly regarded as his oil paintings.

This is also true of Degas’ sculptures: he translated the dancing girls and nudes he had so often drawn and painted into beautifully modelled little figures.

Degas was always an acerbic personality, cruelly witty, aloof and class-conscious. He never married, though he did have a gift for friendship with a happy few. In the 1890s he became increasingly cranky and isolated, but he was able to work until about 1912. His last years were pathetic; he spent much of his time aimlessly wandering the streets of Paris, famous but indifferent to his fame, and almost oblivious to the World War raging to the north.

He died on 27 September 1917.