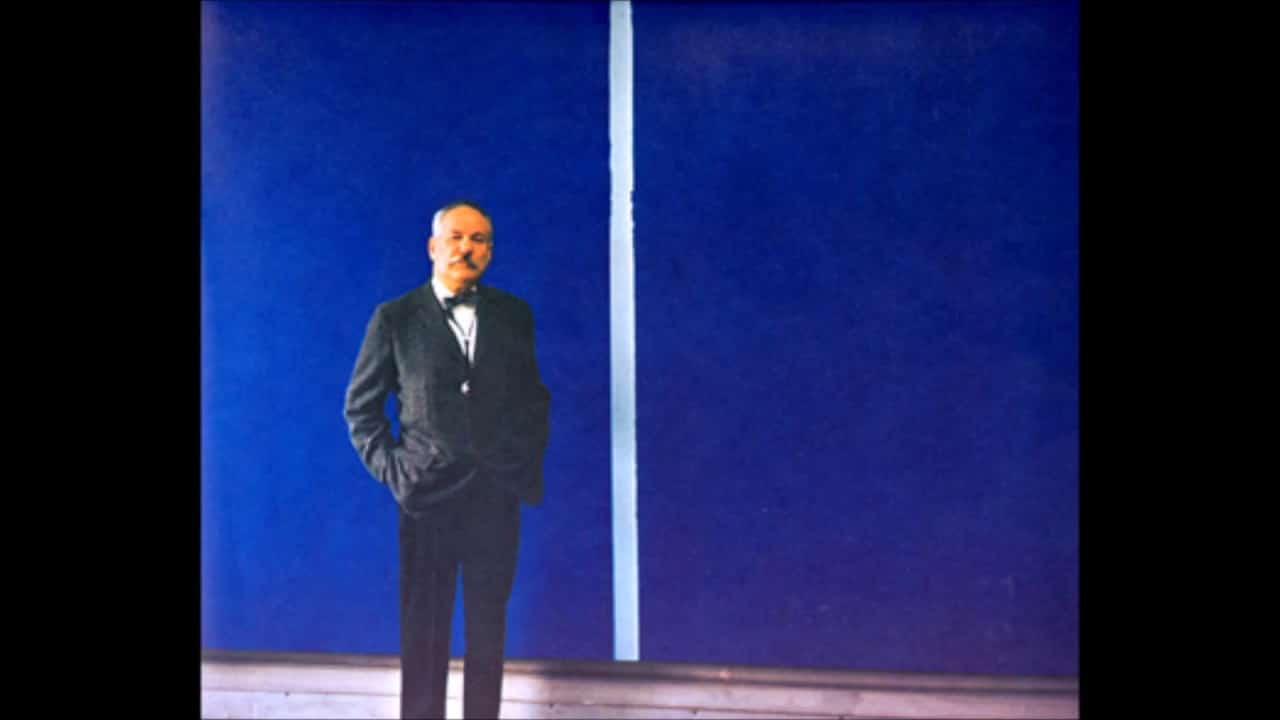

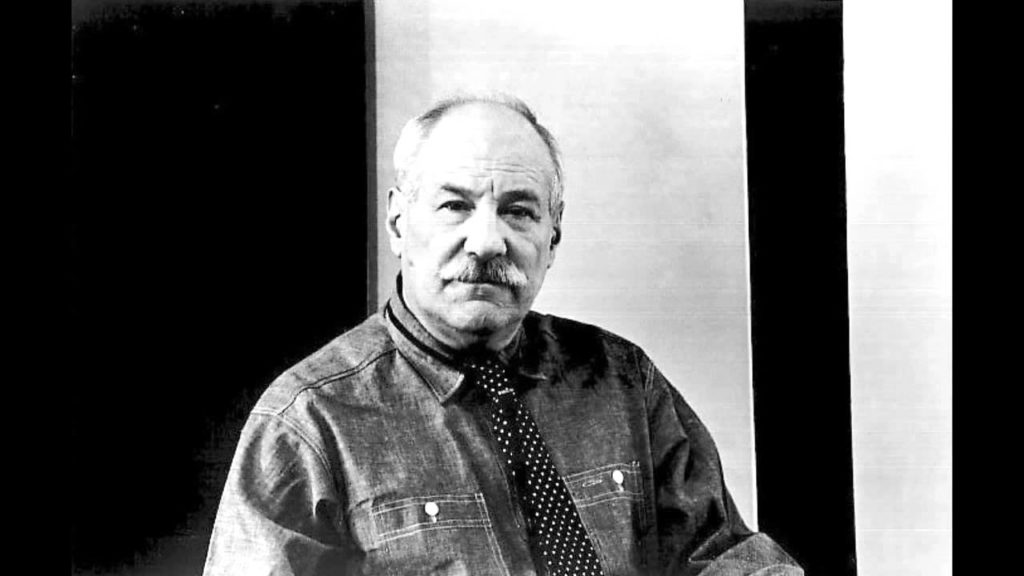

Painter, sculptor, and printmaker. An abstract expressionist who set precedents for color field painting, he is known for enormous solid-color canvases broken only by one or more stripes or “zips,” as he preferred to call them. Like other abstract expressionists, he accepted art as a calling of high seriousness, inherently concerned with existential truths and mystical insights.Nevertheless, the work appealed to younger artists who generally relinquished metaphysics in favor of the reduced expectations of minimalism. Although active in abstract expressionist circles as a theorist and writer during the 1940s, Newman did not have his first one-person show until 1950 and did not attract much interest in his work, even among artists, until the 1960s. A lifelong New Yorker, Newman was given the first name of Baruch, which his parents later Americanized. Everybody called him Barney. Although he began his art studies at the Art Students League in 1922, during his final year of high school, he did not launch a professional art career until more than two decades later. He continued taking drawing classes while attending the City College of New York, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in philosophy in 1927. He then joined a family business, expecting to leave after two or three years to follow his interest in art. However, the Depression dashed those plans, and Newman remained with the firm until 1937. From 1931 until 1947 he also worked as a substitute art teacher in the public schools. In the 1930s, he dabbled in politics, revealing an anarchistic passion for social justice that he never relinquished. He painted off and on in his spare time but later destroyed virtually everything he had done. In the early 1940s he became so interested in botany and ornithology that he studied during the summers of 1940 and 1941 at an Audubon Society camp in Maine and at Cornell University, respectively.

Eventually it was writing, not painting, that made him known among the nascent abstract expressionists. Even when he had temporarily abandoned his own art around 1939–40, he continued to produce unpublished theoretical essays. In 1943 he joined Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb in formulating for publication in the New York Times a classic statement of abstract expressionist intentions, stressing the centrality of “tragic and timeless” subjects. He organized and composed catalogue essays for revealing exhibitions of little known pre-Columbian sculpture in 1944 and Northwest Coast Indian painting in 1946. He also wrote for The Tiger’s Eye . Around 1944 Newman returned purposefully to art making. His first surviving work on canvas dates to 1945, when he was already forty. Like Gottlieb, Rothko, and others in his circle, he was drawn to biomorphic surrealism, in his case enhanced by familiarity with the biological sciences. After joining the Betty Parsons stable in 1946, he took part in several group exhibitions, including “The Ideographic Picture,” which he organized in 1947 to showcase selections by such artists as Rothko and Clyfford Still, along with his own work.

Eventually it was writing, not painting, that made him known among the nascent abstract expressionists. Even when he had temporarily abandoned his own art around 1939–40, he continued to produce unpublished theoretical essays. In 1943 he joined Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb in formulating for publication in the New York Times a classic statement of abstract expressionist intentions, stressing the centrality of “tragic and timeless” subjects. He organized and composed catalogue essays for revealing exhibitions of little known pre-Columbian sculpture in 1944 and Northwest Coast Indian painting in 1946. He also wrote for The Tiger’s Eye . Around 1944 Newman returned purposefully to art making. His first surviving work on canvas dates to 1945, when he was already forty. Like Gottlieb, Rothko, and others in his circle, he was drawn to biomorphic surrealism, in his case enhanced by familiarity with the biological sciences. After joining the Betty Parsons stable in 1946, he took part in several group exhibitions, including “The Ideographic Picture,” which he organized in 1947 to showcase selections by such artists as Rothko and Clyfford Still, along with his own work.

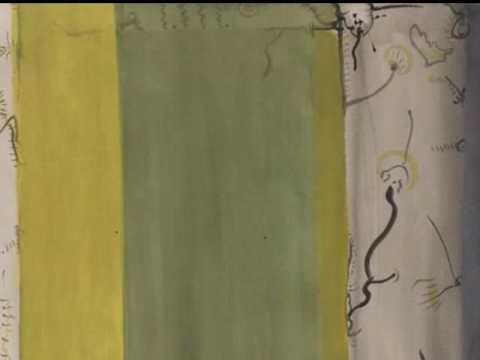

In early 1948 Newman achieved a breakthrough that defined the course of his subsequent art. Onement I (private collection), a dark red field with a lighter, rough-edged, saturated red zip, crystallized the format that he made his own. Energized by his success, he entered the most productive period of his career, completing more than twenty large paintings before his first one-person show in January 1950. Also reflecting his ebullient mood, in December 1948 he published in The Tiger’s Eye an essay titled “The Sublime Is Now,” asserting that American painting had finally shed its European origins to achieve in concrete images an exhilaration surpassing classical beauty. However, the exhibition was poorly received, and the only buyer was a friend of his wife’s. Undeterred, Newman readied for a second show in April 1951 by painting even more audacious works, including one of his best known, the eighteen-foot-wide Vir Heroicus Sublimis (Museum of Modern Art, 1950–51), a red expanse with five zips. The Wild (Museum of Modern Art, 1950), resembling a sculpture hung on the wall, posed even more of a challenge to what a painting might be. Eight feet tall but only one-and-one-half inches wide and deep, it features a centered cadmium red zip, applied with a palette knife, with just barely visible gray-blue at either side. In this exhibition, he also exhibited the plaster of his first sculpture Here I (1950; bronze, 1962), two uprights with a zip of space between. Again, at this show critical reaction proved negative, and nothing sold. Newman withdrew from the Parsons Gallery and generally refrained from showing his work for about seven years. In 1955, despite support from Clement Greenberg in an important article published that spring, after finishing one large painting Newman quit for more than two years. Following a heart attack at the end of November 1957 and a long period of recuperation, in 1958 he returned to work, just as his earlier paintings began to find an appreciative audience. The 1960s saw a complete turnaround in his fortunes, as his work sold for increasingly high prices and he came to be regarded as a leading figure in the New York art world. In 1964 and 1968 he finally had opportunities to travel in Europe. In 1965 he journeyed to Brazil when he and a handful of younger Americans represented the United States in the São Paulo Bienal.

In his final decade, Newman refined and elaborated his zip approach to painting, continued to expand his interest in sculpture, experimented on a limited basis with shaped canvases, and produced lithographed and etched groups of prints. Among the first paintings completed when he returned to painting in 1958 were two of the fourteen related works he collectively titled The Stations of the Cross: Lema Sabachthani . The sensitive manipulation of black and white paint on these austere 6.5 × 5-foot raw canvases provides an aesthetic experience of considerable power. However, even among observers who find in the series emotionally resonant metaphors for human suffering and redemption, some feel that the artist overreached by invoking Christ’s ordeal. While working on this series, Newman also produced his most successful sculpture, the monumental Cor-Ten steel Broken Obelisk , a memorial to Martin Luther King Jr. A tall, upside-down obelisk balances, as if weightless, on the point of a pyramid. At the upper extremity, the tall shaft reaches poignant termination in an irregular break. At the time of his death, Newman was the most widely admired artist of his generation. Younger artists found in aspects of his work the means to escape the hold of abstract expressionism. They responded also to his erudition, verbal prowess, and theoretical sophistication. Ironically, his dictum “Aesthetics is for the artist as ornithology is for the birds” remains a well-remembered epigram. In respect to this claim, however, it is worth recalling Newman’s fondness for the study of birds. Edited by John P. O’Neill, Barnett Newman: Selected Writings and Interviews appeared in 1990.

In his final decade, Newman refined and elaborated his zip approach to painting, continued to expand his interest in sculpture, experimented on a limited basis with shaped canvases, and produced lithographed and etched groups of prints. Among the first paintings completed when he returned to painting in 1958 were two of the fourteen related works he collectively titled The Stations of the Cross: Lema Sabachthani . The sensitive manipulation of black and white paint on these austere 6.5 × 5-foot raw canvases provides an aesthetic experience of considerable power. However, even among observers who find in the series emotionally resonant metaphors for human suffering and redemption, some feel that the artist overreached by invoking Christ’s ordeal. While working on this series, Newman also produced his most successful sculpture, the monumental Cor-Ten steel Broken Obelisk , a memorial to Martin Luther King Jr. A tall, upside-down obelisk balances, as if weightless, on the point of a pyramid. At the upper extremity, the tall shaft reaches poignant termination in an irregular break. At the time of his death, Newman was the most widely admired artist of his generation. Younger artists found in aspects of his work the means to escape the hold of abstract expressionism. They responded also to his erudition, verbal prowess, and theoretical sophistication. Ironically, his dictum “Aesthetics is for the artist as ornithology is for the birds” remains a well-remembered epigram. In respect to this claim, however, it is worth recalling Newman’s fondness for the study of birds. Edited by John P. O’Neill, Barnett Newman: Selected Writings and Interviews appeared in 1990.