Awareness of Classical Greek sculpture (ca. 480–330 B.C.) was for many centuries based upon ancient literary texts describing works of art and statues produced during the Roman Empire that were identified as copies or originals of ancient Greek sculpture. Direct knowledge of Classical sculpture based upon examples found in Greece only began in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries when works like the sculptures from the Parthenon in Athens and the Temple of Apollo at Bassae were brought to the attention of scholars, at times overturning the picture that they had formed indirectly of Greek art. Since that time, the archaeological investigation has produced a complete picture of Classical Greek sculpture, an image that is still developing.

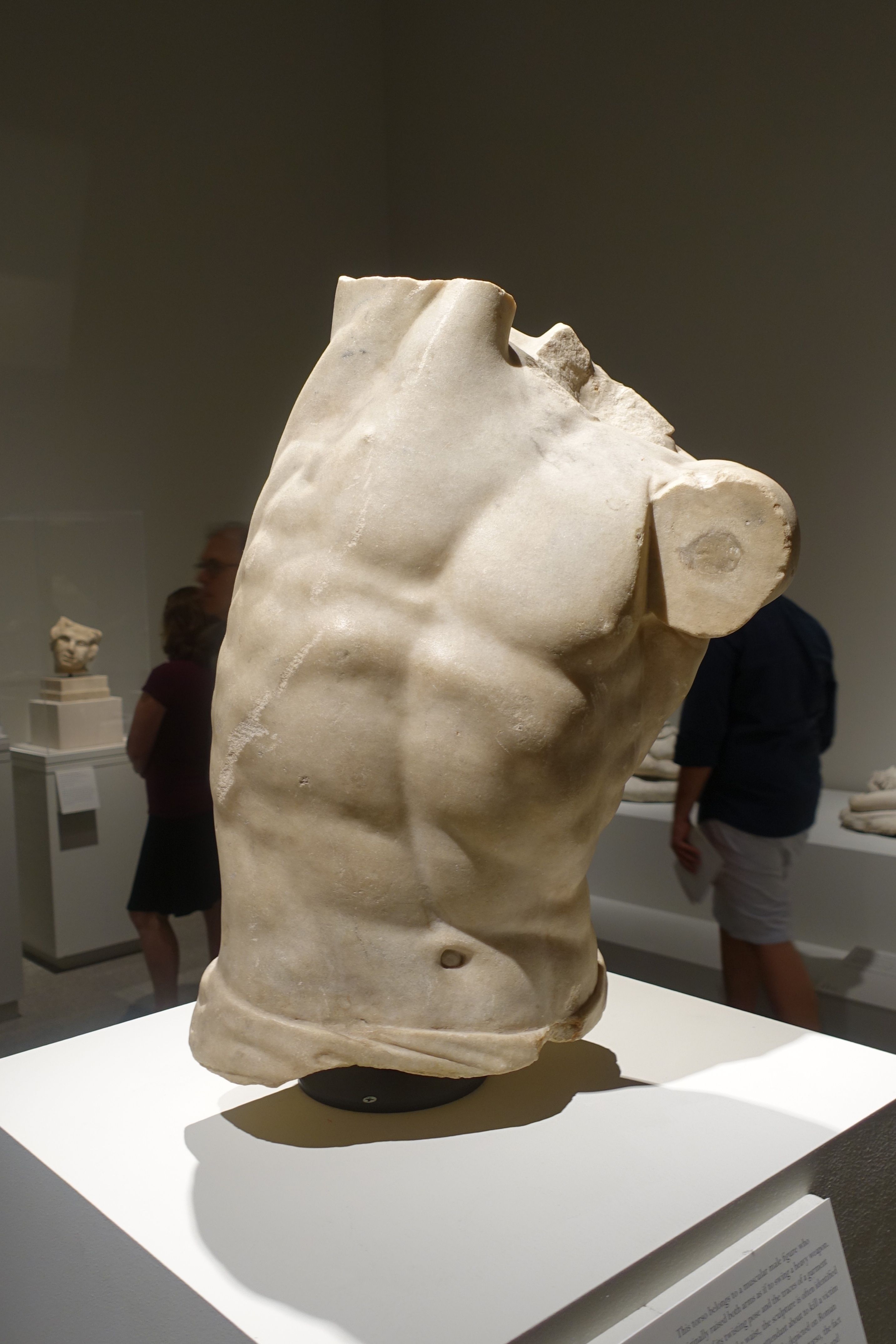

Sculptural works of this period have been regarded since antiquity as precise, beautiful, monumental, balanced, and perfect in their rendering of the human form. The fame of sculptors like Myron, Polyclitus, Pheidias, Alcamenes, Praxiteles, Scopas, and Lysippos is amply attested in ancient literature. These artistic personalities, who defined a naturalistic and idealized style that continued to resonate in later Roman and Renaissance art, have held an enduring interest in the period. However, focus upon the artistic personality, especially in the absence of firmly documented works from their hands, has at times overshadowed the study of the extant material, most of which is unattributed.

Sculptural works of this period have been regarded since antiquity as precise, beautiful, monumental, balanced, and perfect in their rendering of the human form. The fame of sculptors like Myron, Polyclitus, Pheidias, Alcamenes, Praxiteles, Scopas, and Lysippos is amply attested in ancient literature. These artistic personalities, who defined a naturalistic and idealized style that continued to resonate in later Roman and Renaissance art, have held an enduring interest in the period. However, focus upon the artistic personality, especially in the absence of firmly documented works from their hands, has at times overshadowed the study of the extant material, most of which is unattributed.

Context and Typology

The human figure constitutes the central form of Classical sculpture, as found in metal, stone, and terra-cotta statues and reliefs carved on temples, other civic buildings, tombs, and commemorative plaques. Subjects include narratives drawn from mythology, or more rarely from contemporary events like the Battle of Marathon. Frequently, however, myth is used metaphorically, so that a subject like the battle of the Amazons and Greeks symbolizes the struggles of the Greeks with the Persians. Freestanding statues depicted gods and goddesses, heroes, or idealized representations of generic figures. Their purpose ranged from cult statues to votive offerings for victories and other benefices, from symbols of groups or the polis to honorific portraits.

Sculpture from the Classical Period has survived in large numbers, though often in a very fragmentary condition, from a wide range of areas, contexts, and quality. Much has been found in the excavations of religious sanctuaries and public spaces like the agora. The surfaces of stone buildings provided a platform for sculpture, mostly of stone. Sculpture in Doric buildings was concentrated in the pediments and metopes of the superstructure, while in Ionic and Corinthian buildings, pediments, friezes, and the drums of columns were frequently used. Crowning acroterial figures standing on temple roofs were also an integral part of building decorations. In each case, the subject, composition, and pose of the figures had to fit within the confines of the architectural space. This was most problematic in triangular pedimental compositions like those on the Temple of Zeus at Olympia (470–457 B.C.), the Parthenon (437–432 B.C., and the Temple of Asclepius at Epidauros (380–370 B.C.). A progression of standing, striding, seated, and reclining figures from the center to corner provided a unity of scale, but an overall integration of design and composition resulted from the ability to show emotion and reaction among the figures.

Sculpture from the Classical Period has survived in large numbers, though often in a very fragmentary condition, from a wide range of areas, contexts, and quality. Much has been found in the excavations of religious sanctuaries and public spaces like the agora. The surfaces of stone buildings provided a platform for sculpture, mostly of stone. Sculpture in Doric buildings was concentrated in the pediments and metopes of the superstructure, while in Ionic and Corinthian buildings, pediments, friezes, and the drums of columns were frequently used. Crowning acroterial figures standing on temple roofs were also an integral part of building decorations. In each case, the subject, composition, and pose of the figures had to fit within the confines of the architectural space. This was most problematic in triangular pedimental compositions like those on the Temple of Zeus at Olympia (470–457 B.C.), the Parthenon (437–432 B.C., and the Temple of Asclepius at Epidauros (380–370 B.C.). A progression of standing, striding, seated, and reclining figures from the center to corner provided a unity of scale, but an overall integration of design and composition resulted from the ability to show emotion and reaction among the figures.

Inside the temple were freestanding statues, including cult images. The chryselephantine statues of Athena for the Parthenon and of Zeus for his temple at Olympia by Pheidias, whose workshop at Olympia was found in excavations, were two of the most elaborate made during this period. The written testimony of ancient viewers reveals the feelings of wonder and awe that such statues were meant to invoke. Unfortunately, most of these cult statues, frequently made of valuable materials, have been lost, while the architectural sculptures that do survive attracted less attention initially.

The desire to leave an enduring public testimony to an individual or accomplishment resulted in votive and honorific statues. These include single figures or groups, including chariot teams, and represent either mythological, eponymous, or generic subjects or specific individuals. During the Classical Period, these statues were frequently done in bronze and have disappeared, although bases for these statues found in excavations reveal some information about their original position and purpose. Many of these statues were cast in bronze, using the more complicated and multiple-step lost-wax method that was perfected during the Classical Period. Examples of large-scale sculpture in this material are quite small due to the frequent melting of statues for their valuable metal material, but in some cases, their stone bases survive. Discoveries of bronze sculpture through excavation, mainly of ships lost at sea, have provided some material for the study of style and techniques in that medium.

The desire to leave an enduring public testimony to an individual or accomplishment resulted in votive and honorific statues. These include single figures or groups, including chariot teams, and represent either mythological, eponymous, or generic subjects or specific individuals. During the Classical Period, these statues were frequently done in bronze and have disappeared, although bases for these statues found in excavations reveal some information about their original position and purpose. Many of these statues were cast in bronze, using the more complicated and multiple-step lost-wax method that was perfected during the Classical Period. Examples of large-scale sculpture in this material are quite small due to the frequent melting of statues for their valuable metal material, but in some cases, their stone bases survive. Discoveries of bronze sculpture through excavation, mainly of ships lost at sea, have provided some material for the study of style and techniques in that medium.

Several other types of smaller-scale sculptures also existed. Small terra-cotta figurines and plaques are found in large numbers in sanctuaries as votive offerings and are functionally similar to the larger-scale votive statues of bronze and stone. These works were mass-produced from molds and then painted, constituting a more affordable type of dedicatory work. Although these figures are not as precise and carefully produced as larger-scale sculpture, their style and composition parallel developments in more significant media and show the diffusion of the style and ideals of Classical art to a broader level of society. Relief plaques in stone were made for graves or to commemorate a specific event or document. Grave reliefs usually show the deceased in an idealized manner, sometimes surrounded by members of the household. Laws against personal extravagance occasionally suspended production of this type of work, but there are numerous examples coming from Attica in the later Classical Period. Commemorative reliefs often combine an image of heroic or mythological nature with an inscription below. These works are important because they sometimes provide a date derived from the text for their creation, giving a fixed point for the development of style in sculpture.

Style

Classical Greek sculpture is distinguished from the arts of other cultures of the ancient Mediterranean and Near East by its form. A notable feature of this style is its mimetic or naturalistic quality: The sculpted figure approximates the appearance and movements of the real human figure, rather than relying upon a series of more abstract conventions. For example, statues, rather than standing squarely on both feet as in the Archaic Period, place the weight on one leg (contrapposto), leaving the other leg free and introducing asymmetries into the figure. The classical sculpture is idealized, utilizing systems of proportions, balance, and expression that bring order, serenity, and completeness to the figure.

The style in Greek sculpture is less fixed than in many other periods and cultures and shows a relatively steady and rapid progression. In the Early Classical Period (ca. 480–450 B.C.), figures display a more naturalistic sense of movement than in the Archaic period, exploring the patterns of movement and adjustment in the body in the performance of an action, encapsulated in the Greek term rhythmos and seen in works like the Kritios Boy from the Acropolis in Athens. Sculptors also focused upon facial expression, gesture, and attitude to convey emotion or pathos, giving the figure a psychological movement in addition to physical action. These developments allowed the artist to explore the character (ethos) of the figure. Some of the most prominent examples of this can be seen in the sculptures from the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, found in the excavations of 1876 to 1882, but still presenting problems in the reconstruction of their original placement, and in the bronze figure known as Riace Warrior A, found in a shipwreck off the coast of Italy in 1972. The figures for this phase have solidity and simplicity of surface that has led to the term “Severe Style” for this period.

The style in Greek sculpture is less fixed than in many other periods and cultures and shows a relatively steady and rapid progression. In the Early Classical Period (ca. 480–450 B.C.), figures display a more naturalistic sense of movement than in the Archaic period, exploring the patterns of movement and adjustment in the body in the performance of an action, encapsulated in the Greek term rhythmos and seen in works like the Kritios Boy from the Acropolis in Athens. Sculptors also focused upon facial expression, gesture, and attitude to convey emotion or pathos, giving the figure a psychological movement in addition to physical action. These developments allowed the artist to explore the character (ethos) of the figure. Some of the most prominent examples of this can be seen in the sculptures from the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, found in the excavations of 1876 to 1882, but still presenting problems in the reconstruction of their original placement, and in the bronze figure known as Riace Warrior A, found in a shipwreck off the coast of Italy in 1972. The figures for this phase have solidity and simplicity of surface that has led to the term “Severe Style” for this period.

In the succeeding High Classical phase (450 to 430 B.C.), artists perfected their rendering of the anatomy and included more detailing and modeling of the modeling surface. The figures convey more effectively the impression of motion that has been frozen in time and space and display a serene and contained expression that turns away from the earlier interest in pathos and is more evocative of a perfected ideal often referred to as Olympian. The transition to the High Classical style and its development can be seen in the Parthenon, dated from the inscribed building accounts to the years 447 through 432.

Late Classical sculpture between 430 and 400 B.C. develops a more decorative and sensual style. The figures of Victory (Nike) on the balustrade from the Temple of Athena Nike on the Acropolis portray a new kind of sensuality and refinement through transparent draperies that reveal the figure underneath and with intimate poses and situations, found more broadly in grave reliefs and vase paintings of the time.

The sculpture of the fourth century shows more diversity in style. An intense emotionalism, associated with Scopas, can be seen in the sculptures from the temples at Epidauros and Tegea and in some of the figures from the Mausoleum at Halikarnassos. The strong lines, sharp movement, and deep undercutting of this work forms a sharp contrast to the smoother surfaces, variations of textures, and more languorous poses of the Hermes from Olympia, once identified as an original of Praxiteles. Praxiteles also created one of the most famous statues in antiquity, the cult statue of Aphrodite at Cnidus, known only from copies. A third tendency in the fourth century was toward a greater realism of detail and fidelity toward the appearance of real life that is associated with Lysippos, whose work is linked with the Agias from the Daochos Monument found at Delphi and the bronze Getty Athlete. The development of psychological portraiture and of a dramatic sense of composition can also be linked to Lysippos, making him a transitional figure between Classical and Hellenistic art.

The existence of fixed consecutive points for some works and the developmental nature of style in Classical sculpture provide criteria for dating works and contexts without written documentation. Although this model has come under some criticism in recent years, it is generally sound. Problems with this model lie in the copies produced of classical works in the Roman Empire, which do not precisely replicate the original, and in the phenomenon of revivals of older styles, which begins to appear in the fifth century and which expands from that point onward. Determining whether a work is Classical or classicizing can frequently create problems for determining the date of associated works and material from a context.