Edouard Manet was regarded in his time as the leader of the French Impressionists. He was one of the first to develop the technique of short, expressive brushstrokes and strong lighting, using his painting to portray the fashions and manners of his day in an outgoing, spontaneous way.

“There is only one true thing: instantly paint what you see. When you’ve got it, you’ve got it. When you haven’t, you begin again. All the rest is humbug”.

Edouard Manet was one of the leaders of the 19th century revolution in art, ridiculed and abused for most of his career as an arch-rebel. In a period of slick ‘chocolate-box’ art, full of false heroics and sugary sentiments, Manet was the supreme ‘painter of modern life’, devoted to portraying Parisian fashions and manners.

But his pictures are works of art, not documentaries. His compositions are often witty variations on traditional designs, but he rejected the literal, ‘photographic’ style of his contemporaries and created an art of bold colors and contrasts, with cursorily painted passages that contemporaries regarded as skimpy but which we now see as exciting and energizing.

Spontaneous and artful, ultra-modern and traditional, Manet’s art bewildered his own generation, but has been a source of delight to the 20th century.

Edouard Manet was born in Paris on 23 January 1832. His background was upper-middle-class (his father was a senior civil servant) and, by contrast with many of his bohemian friends, Manet was always a polished gentleman and something of a dandy, very much at ease in good society.

He was distressed and sometimes discouraged by the hostility shown towards his work, and always hoped for popular and official recognition – though he was evidently tougher than is sometimes supposed, since he refused to modify his style for the sake of success.

Manet was allowed to become a painter after a double failure, at school and as a naval cadet. He studied dutifully under a well-known master, and in 1861 had one of his painting The Spanish Singer, accepted by the jury of official Salon. Since the Salon was virtually the only place where an artist could hope to have his work seen by large numbers of people, this was a first step in what might have become a conventionally successful career.

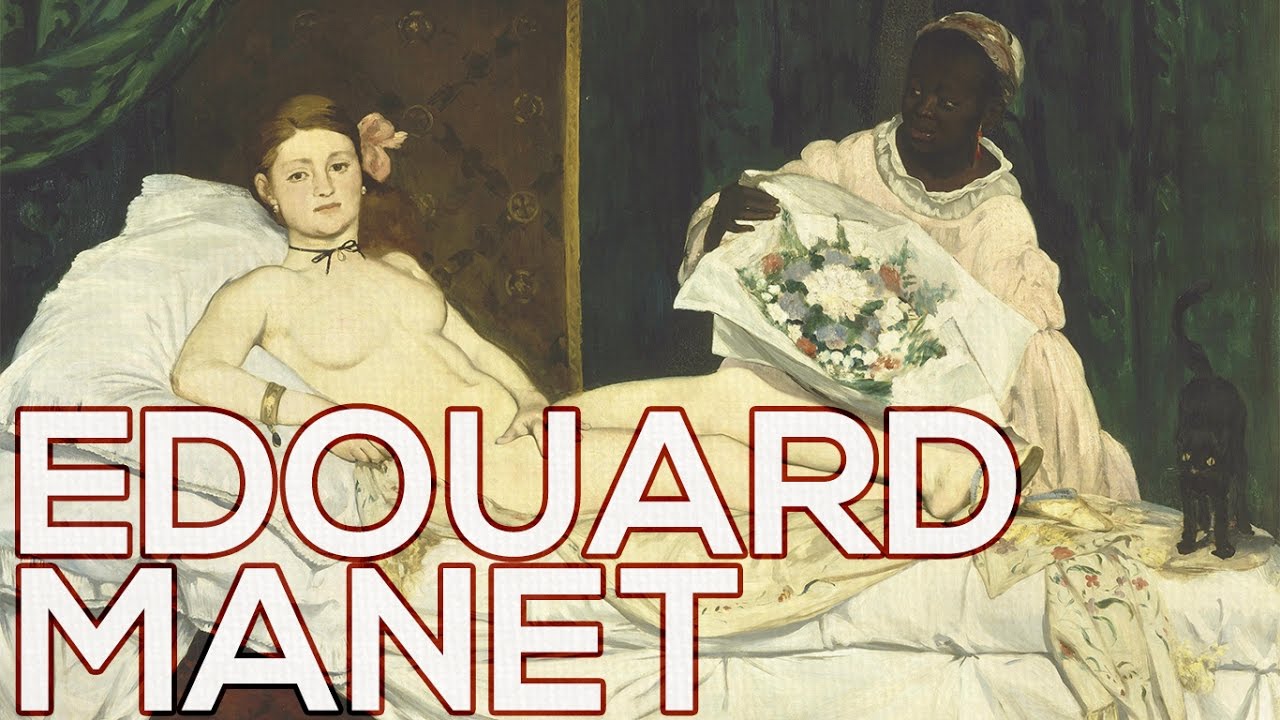

But Manet’s conventional prospects were soon put in doubt when he started painting ‘modern’ pictures like Music in the Tuileries. None of his submissions to the 1863 Salon were accepted, but there were so many dissatisfied artists that the Emperor Napoleon III permitted an exhibition of rejects, the Salon des Refusés, to run concurrently with the official Salon. Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass caused a scandal at the Refusés, and worse was to come when his Olympia was shown at the Salon two years later. Manet’s chief offence was to exhibit naked, obviously modern young women; his respected contemporaries actually painted far more erotic nudes, but in safely ‘classical’ settings that made them less ‘vulgar’ and disturbing.

In the 1860s Manet became recognized as the leader of the younger generation, and fellow-rebels such as Edgar Degas and Claude Monet often gathered round him at the Café Guerbois and other haunts. But in 1874, when they organized a group exhibition – later known as the first Impressionist Exhibition – Manet remained aloof, continuing to believe that ‘the Salon is the real field of battle’. However, contact with Monet did encourage him to experiment with painting out of doors and, more consistently, to use bright colors.

In 1878 Manet began to suffer from pains in the legs, the symptoms of the nervous disease locomotor ataxia; the cause was certainly an early infection of syphilis, a scourge that was the 19th century counterpart of AIDS.

Manet worked with increasing difficulty, producing a last masterpiece, Bar at the Folies Bergere, and continuing to paint flower-pieces almost to the end. On 14 April 1883 his left leg became gangrenous and had to be amputated, but the operation failed to save him.

Edouard Manet died 16 days later, still only 51 years old.